Gold has captivated human societies for thousands of years. Its lustrous beauty, rarity, and malleability made it an object of desire and a symbol of power across cultures. But when and where did humans first learn to work this precious metal? Archaeological evidence now suggests that the fifth millennium BC, in what is today Bulgaria, marks the time and place of the earliest processed gold in the world. This article explores the remarkable Varna Necropolis finds in Bulgaria – the oldest known gold treasure – and compares them with other ancient gold discoveries in Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, the Americas, and beyond. We will examine how these early cultures utilized and valued gold, highlighting both the similarities in its ceremonial prestige and the differences in the technologies and traditions surrounding this timeless metal.

Varna Necropolis (Bulgaria, 5th Millennium BC): The Oldest Gold Treasure

Archaeologists excavating the Varna Necropolis in the 1970s uncovered dozens of graves containing stunning gold artifacts. The Varna site, dated to around 4600–4200 BC, has yielded the world’s oldest processed gold objects. Over 3,000 gold items were found in 294 tombs, with a total weight of about 6 kilograms, indicating an unexpected level of wealth and craftsmanship in Europe’s late Stone Age.

The Varna Necropolis, accidentally discovered in 1972 near Lake Varna, Bulgaria, astonished the world with its sheer quantity of ancient gold jewelry and ornaments. Radiocarbon dating places the burials roughly between 4560 and 4450 BC, a time long before the rise of the Egyptian pharaohs or Mesopotamian cities. The people of this Chalcolithic (Copper Age) Varna culture were among the first to master metalworking, not only in copper but also in gold. The site’s excavators unearthed bracelets, necklaces of beads, earrings, zoomorphic figures, gold plaques, and diadems, all carefully arranged in the graves. The workmanship is excellent: Varna goldsmiths shaped the metal through hammering, cutting, and piercing techniques, which bespeak a high level of technology for the time. Archaeologists have noted that the Varna gold finds exceed the combined number and weight of all other gold artifacts of the 5th millennium BC discovered worldwide. One elite burial in particular, known as Grave 43, contained 990 gold objects weighing approximately 1.5 kilograms – more gold than in all other contemporary sites of that era combined. This grave belonged to a tall, high-status male (often dubbed the “Varna man”), who was buried with an array of symbols of power: thick gold bracelets, a multi-strand gold bead necklace, gold pendants and disks sewn onto his garments, a gold-covered scepter/axe, a long flint blade (sword), and even a gold sheath that covered his genitalia. Such opulence in a single tomb makes it the richest known grave of the Copper Age anywhere in the world.

Intriguingly, not all Varna burials were equal – most had far fewer grave goods, and some lacked skeletal remains altogether. The richest graves, including some symbolic cenotaphs with no remains, had the lion’s share of the gold, while others were relatively impoverished. This suggests that the Varna society was socially stratified, with emerging chiefs or priestly leaders accumulating wealth and status. Grave 43’s occupant, for example, is thought to have been a chieftain or high priest, and at one time was even hypothesized to be a metallurgist or smith, given the presence of copper tools in the grave. The spiritual and ceremonial role of gold is evident: some graves without bodies contained clay masks or faces adorned with gold ornaments – possibly offerings for community members who died elsewhere, indicating a ritual use of gold in honor of the deceased. The metal itself was incredibly pure (estimated at 23.5–24 karat), which has prompted speculation about how these prehistoric people achieved such purity, perhaps by naturally sourcing high-quality alluvial gold from nearby rivers. In any case, the Varna hoard reflects a sophisticated culture with long-distance trade, as evidenced by the presence of shells from the Aegean and high-quality flint from remote sources in the tombs, as well as a developed aesthetic sense. The discovery at Varna fundamentally overturned the notion that Old Europe in the 5th millennium BC was a simple, egalitarian farming society – clearly, complex social networks and wealth accumulation were already in place.

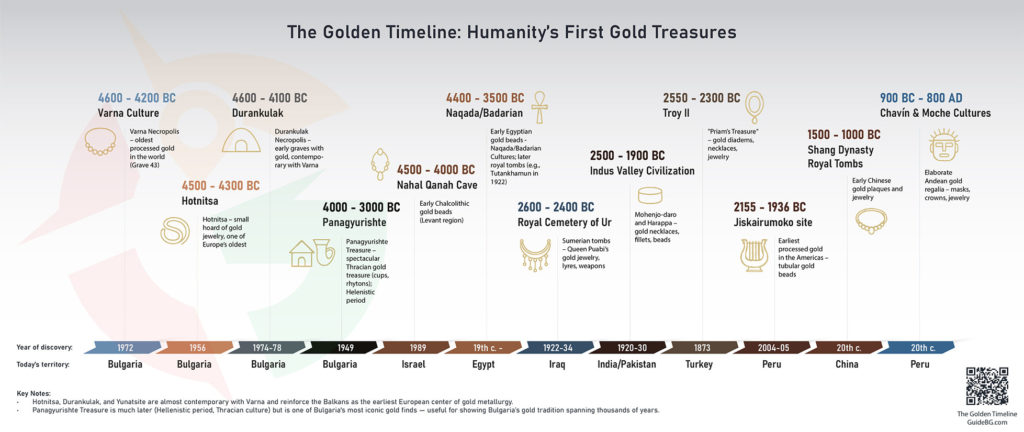

It is worth noting that Varna is not an isolated example in the region. Other Bulgarian and Balkan finds of similar age, such as the gold objects from Hotnitsa, Durankulak, and the Yunatsite settlement, have also been dated to the late 5th millennium BC. These sites, though yielding fewer pieces, support the idea that Southeastern Europe was a cradle of early gold metallurgy. Still, the Varna Necropolis treasure is the largest and most diverse, hence it is widely celebrated as the oldest golden treasure in the world. The trove is now exhibited in the Varna Archaeological Museum, where it continues to awe visitors and researchers alike with its age and splendor.

Gold ornaments from a Varna cenotaph burial (a ritual grave with no human remains) are on display at the Varna Museum. These artifacts – including a gold diadem, circular appliqués, bracelets, and beads – were crafted around 4500 BC. The Varna goldsmiths shaped native gold by hammering and polishing, achieving a high level of artistry long before the advent of large urban civilization.

Ancient Egypt: Gold of the Pharaohs (c. 4000–1500 BC)

While the Varna culture was flourishing in Europe, the people of Predynastic Egypt were also beginning to appreciate and work with gold, though evidence from the earliest periods is sparse. Small gold beads and jewelry appear in the Badarian and Naqada cultures (4th millennium BC) in Egypt. By around 3100 BC, the time of Egypt’s First Dynasty, gold had become a symbol of royalty and divinity. Tellingly, the Egyptian word for gold, nbw, appears in hieroglyphs from the earliest inscriptions. Early Egyptian gold artifacts tend to be modest (due to many being lost or melted over time), but a few survived; for instance, a small gold bangle from the tomb of King Khasekhemwy (c. 2700 BC) is one of the rare pieces from the Early Dynastic period. By the Old Kingdom (27th–25th centuries BC), Egyptian goldsmiths were creating astonishing works. A famous example is the funerary collection of Queen Hetepheres (c. 2600 BC) – mother of Khufu (the Great Pyramid’s builder) – which included gilded furniture and fine gold craftwork, indicating that sophisticated goldsmithing was already present by that time. Egyptian craftsmen had mastered techniques like hammering gold into thin sheets, lost-wax casting, and soldering by the third millennium BC. They often alloyed gold with silver (natural electrum) or left it unrefined, resulting in varying hues of gold in artifacts.

What truly distinguishes ancient Egypt’s relationship with gold is its deeply religious and ceremonial significance. Gold was regarded as the “flesh of the gods,” especially associated with the sun deity (Ra) due to its radiant shine. This belief led the Egyptians to use gold copiously in funerary contexts: pharaohs and elites were buried with vast gold riches to ensure a blessed afterlife. Royal tombs from the Old and Middle Kingdoms contained gold jewelry, amulets, and gilded coffins, although many were later looted. In the New Kingdom (16th–11th centuries BC), Egyptian gold craftsmanship reached its zenith, as evidenced by the treasures of Tutankhamun (1323 BC) – notably his solid gold funerary mask and inner coffin weighing over 110 kg of gold. Although Tutankhamun’s tomb dates back much later than the focus of this article, it exemplifies the long tradition of Egyptian gold work that had its roots in the early experiments of millennia past. By Tut’s time, goldsmiths could produce intricate granulation (soldering tiny gold beads onto jewelry) and cloisonné inlay with gemstones, far beyond the simpler hammered beads of the 4th millennium BC.

In terms of source, Egypt was rich in gold deposits. The metal was mined from the Eastern Desert and Nubia (Kush) to the south. Egyptian expedition records and inscriptions from the Old Kingdom onward mention gold quarrying, showing an organized effort to supply the royal workshops. The abundance of gold made it a symbol of divine and kingly power – pharaohs offered gold gifts (the famous phrase “gold of honor”) to loyal officials, and temples amassed gold for their rituals. By comparing Egypt with Varna, we observe a common thread: in both cultures, gold was associated with notions of eternity and status – Varna’s people sent their elite into the afterlife laden with gold, and similarly, the Egyptians did on a much larger scale. However, scale and continuity differ: Egypt’s use of gold became state-organized and industrial over time, whereas Varna’s was a shorter-lived florescence. Still, both are among the earliest chapters of humanity’s obsession with gold.

Mesopotamia: Gold in the Cradle of Civilization (c. 3000–1500 BC)

In the ancient land of Mesopotamia, known as the “Cradle of Civilization” between the Tigris and Euphrates, gold appears in the archaeological record by the early third millennium BC. The Sumerians of southern Mesopotamia did not have abundant local gold sources, but through trade and conquest, they acquired gold and regarded it as a highly precious material. The most spectacular evidence comes from the Royal Cemetery of Ur, located in modern Iraq, dating to around 2600–2400 BC. Excavations by Sir Leonard Woolley in the 1920s at Ur uncovered the tombs of Sumerian royalty and elites filled with treasures. Among these were astonishing gold artifacts: gold helmets (one exquisite example, believed to belong to King Meskalamdug, was pounded out of a single sheet of gold to mimic a wig or haircap), harps and lyres decorated with gold (including a famous bull-headed lyre with a gold and lapis lazuli bull’s head), gold daggers and swords, gold drinking cups and bowls, and elaborate jewelry such as headdresses, earrings, necklaces and diadems made of gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian. One celebrated example is the tomb of “Queen” Puabi at Ur – her skeleton was adorned with an elaborate gold headdress composed of multiple gold floral ornaments and ribbons, along with large gold earrings and strings of beads; on her shoulders and chest were cape-like arrangements of gold leaves, beads, and pendants. Her attendants in the tomb also wore gold adornments.

The craft techniques in Mesopotamia by this time were highly advanced. Goldsmiths could cast objects by the lost-wax process – archaeologists infer this from finds like an electrum (gold-silver alloy) dagger blade that appears to have been cast, demonstrating fully developed casting practices in Sumerian workshops. At the same time, many items were made by hammering: for instance, the gold helmet and some bowls were beaten from solid lumps of gold. Twisted gold wire was used to form handles of cups and to create intricate jewelry chains. Mesopotamian artisans even practiced early forms of filigree and granulation, soldering tiny gold wires or balls onto objects for decoration, and they inlaid precious stones into gold settings. The variety of gold items at Ur – from weapons and tools to musical instruments decorated with gold – suggests that gold had permeated both sacred and secular spheres. It signified both ritual wealth (many of these objects were likely used in ceremonies or as regalia) and the opulence of the ruling class.

Culturally, the Mesopotamians valued gold as a symbol of rank and as an offering to the gods. Mesopotamian temples housed statues of deities that were sometimes covered in gold leaf. An example is the cult statue of Marduk in Babylon from later periods, which was reportedly made of gold. In earlier Sumer, we have indirect evidence of this reverence: one of the artifacts from Ur is the so-called “Ram in a Thicket”, a figure of a ram standing against a tree, made of wood but entirely overlaid with gold foil and lapis lazuli – likely a devotional piece. The fact that Sumerian graves, such as those at Ur, contain such lavish gold items indicates a belief in an afterlife where these items might be needed or, at the very least, a desire to display one’s wealth and piety at death, much like in Varna and Egypt. However, unlike Egypt, Mesopotamia’s early civilizations did not leave their gold treasures intact – many were looted in antiquity or later. The Royal Cemetery of Ur is a rare glimpse, where, in one case, a wealthy tomb (that of Puabi) escaped looting, giving us a snapshot of Sumerian wealth. Chronologically, the Mesopotamian gold artifacts postdate the Varna gold by approximately 1,500-2,000 years, yet they demonstrate an independent flowering of gold-working knowledge. Whether the idea of crafting gold spread from the Balkans to Mesopotamia or arose independently is uncertain; by 3000 BC, multiple centers of metallurgy existed in Europe and Asia. In any event, gold was firmly entrenched in the elite cultures of the Near East by the Bronze Age, used in everything from royal burials to temple treasuries.

Indus Valley: Harappan Gold and Artisan Traditions (c. 2500–1900 BC)

Far to the east, the urbanized society of the Indus Valley Civilization (Harappan Civilization, in present-day Pakistan and northwest India) was also working gold by the mid-third millennium BC. The Indus civilization (2600–1900 BC) was contemporary with the Akkadian and Old Babylonian periods in Mesopotamia and the Old Kingdom to Middle Kingdom in Egypt. Archaeological excavations at the great Indus cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa have unearthed numerous gold objects, testifying that gold was a valued commodity in this culture as well. The types of Indus gold artifacts include jewelry like bangles, necklaces, head ornaments, rings, earrings, and beads. For example, excavators have found thin fillets of finely hammered gold that would be worn across the forehead, and necklaces composed of gold beads alternating with semi-precious stones (carnelian, turquoise, jade, etc.), showcasing a sophisticated sense of design. One extraordinary find is a seven-strand necklace from Mohenjo-daro (c. 2400–2000 BC) which was so admired that when India and Pakistan split in 1947, the piece was divided between the two nations’ museums. This necklace originally featured 55 gold beads plus jade and stone beads, strung on a gold wire, with intricate gold spacer disks made by soldering two half-spheres together (a fairly advanced technique). The gold beads in Indus jewelry were often hollow (formed by joining halves) or tubular and required considerable skill to produce uniformly. Indus craftspeople were clearly adept at goldsmithing: they could hammer gold into thin sheets, draw it into wire, and even perform basic soldering to create composite beads – abilities on par with their Mesopotamian and Egyptian counterparts.

However, the cultural context of gold in the Indus Valley appears to differ from that in Egypt or Sumer. Notably, the Indus people did not typically bury gold (or other valuables) with their dead. Indus burial sites are relatively austere, lacking the lavish tomb offerings seen elsewhere. Instead, precious ornaments were probably passed down or hidden. Archaeologists have found jewelry hoards within city dwellings – for instance, treasures of gold and semi-precious stone ornaments were discovered concealed under the floors of houses in Mohenjo-daro. One explanation is that Indus society may have placed less emphasis on displaying wealth in funerals; gold was a sign of social status and wealth, but it stayed among the living or was cached for safekeeping, perhaps in times of crisis. This is evidenced by the fact that “such ornaments were never buried with the dead, but were passed on from one generation to the next” and often found hidden in homes of the affluent or in the quarters of jewelers. This practice contrasts with Varna, Egypt, and Sumer, where tombs yielded most of the gold artifacts. The Indus approach suggests a cultural norm of preserving wealth within the community or family rather than sacrificing it in burials.

Despite the different customs, the prestige of gold in the Indus civilization was likely as high as elsewhere. Indus cities were major centers of craft and trade, and they had commercial links with Mesopotamia. Mesopotamian records mention trade with “Meluhha” (believed to be the Indus region), and a carnelian bead necklace from Queen Puabi’s tomb at Ur was found to include beads likely made in the Indus Valley. While Mesopotamian texts don’t explicitly list gold from Meluhha, the presence of Indus-made ornaments in Mesopotamia hints that inter-regional exchange of precious materials occurred. The Indus people could have obtained gold from a variety of sources: deposits in the Himalayas, Afghanistan, or southern India (there were goldfields in ancient India, such as Kolar, though whether Harappans reached them is uncertain). What is clear is that by 2500–2000 BC, Indus goldsmiths were creating jewelry of remarkable elegance, rivaling the craft quality seen in royal tombs of other lands, even if the items come to us through different archaeological contexts.

In summary, the Indus Valley presents a case where gold served as a significant marker of wealth and aesthetics in a highly urbanized society. Yet its ritual and funerary role was muted compared to the civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, or Varna. This difference underscores the diverse cultural attitudes towards wealth: to the Harappans, jewelry might have been as much a trade good and personal asset as a ritual treasure. They left behind fewer spectacular hoards for archaeologists, but enough fragments to show that the allure of gold had spread across the ancient world by the third millennium BC, reaching even the far corners of South Asia.

Ancient Americas: Early Andean Gold (c. 2000–500 BC)

Across the ocean in the New World, the story of gold takes a later, yet no less fascinating turn. In the Andes of South America, gold working began independently of the Old World. The earliest known gold artifacts in the Americas are significantly later than those of the Old World, appearing in the late 3rd to early 2nd millennium BC. Until recently, the oldest discovered gold in the Americas was found at a site called Jiskairumoko in the Peruvian Andes, near Lake Titicaca. There, archaeologists uncovered a momentous yet straightforward find: a small necklace with nine gold beads in a burial context, dated to roughly between 2155 and 1936 BC. This necklace was discovered in a relatively modest village inhabited by early agrarian people, essentially a community in transition from hunter-gatherer lifeways to more settled farming practices. The gold beads are tubular and were made by cold-hammering naturally occurring gold nuggets into flat sheets, then rolling them into cylinders. The craftsmanship is described as somewhat crude (the beads show hammer marks and irregular edges), indicating that the techniques were still developing. Nevertheless, the very presence of worked gold at Jiskairumoko is astonishing: it shows that even without large cities or states, these early Andean people recognized the value of gold and crafted it into ornamentation. As archaeologist Mark Aldenderfer, who led the discovery, noted, this challenges the assumption that only complex, stratified societies produce prestige goods – here were simple villagers creating the New World’s first gold jewelry as symbols of emerging status and ritual.

The find at Jiskairumoko pushes back the timeline of gold working in the Americas and suggests that by 2000 BC, social differentiation was underway in the Andes (the gold necklace likely signified the special status of the person buried with it). After this point, evidence of gold use in Andean South America becomes more plentiful in the archaeological record of the Initial Period and Early Horizon (c. 1800–500 BC). For instance, in Peru’s Chavín culture (~900–500 BC), gold was fashioned into elaborate ornaments, crowns, and religious iconography. A notable piece is the Chavín crown or headdress found at the site of Chavín de Huántar, hammered from gold foil. Similarly, slightly later cultures like the Moche (c. 100–800 AD) on the Peruvian coast became master goldsmiths, creating breathtaking work such as gold face masks, headpieces, and jewelry inlaid with turquoise – though these are over two millennia later than the first Andean gold beads.

One interesting aspect of ancient American gold is its ceremonial use. In the Andes, gold (and silver) eventually came to be associated with cosmic symbolism. For the Inca, gold was later referred to as the “sweat of the sun” and held strong religious significance. Even in these earliest instances at Jiskairumoko, we suspect that gold wasn’t used for tools or currency but purely for display and ritual importance, much like in the Old World. The technology path in the Americas also mirrored that of the Old World to some degree: initial simple hammering and annealing, and later the development of casting and alloying (by 1000 BC, Andean smiths were mixing gold with copper to form tumbaga and experimenting with casting). Yet, what’s notable is that the rise of gold-working in Peru predates the rise of big cities there. The Jiskairumoko case shows that a humble hamlet could produce a gold item centuries before the grand temples of Chavín or the royal tombs of Sipán (Moche) filled with golden masterpieces. In that sense, it parallels Varna: a relatively small-scale society achieving a first with gold, underscoring a kind of universal human attraction to the metal. As one scholar remarked, “Gold certainly is one of those things in human history that has attracted the eye… people see it as something unique and different.” – a statement that could apply equally to the Varna chief, an Egyptian pharaoh, or a tribal leader in the ancient Andes.

Other Early Gold Finds: Anatolia and Beyond

In addition to the primary centers discussed above, other parts of the ancient world also discovered gold and worked it in early times. In Anatolia (modern Turkey), for example, archaeologists have found early gold artifacts at sites like Troia (Troy). The legendary city of Troy (Ilium) was a Bronze Age settlement, and in the level known as Troy II (circa 2550–2300 BC), a spectacular cache of gold and jewels was uncovered by Heinrich Schliemann in the 19th century. Schliemann dubbed it “Priam’s Treasure” (after the Homeric king of Troy), although it is now known to be much earlier than the Trojan War era, roughly contemporary with the flourishing of the Indus Valley and Akkadian Mesopotamia. This hoard included dozens of gold diadems, necklaces of gold beads, gold earrings, and other ornaments. One famous piece is a large gold diadem or forehead ornament made of intertwined chains and pendants. The Troy finds demonstrate that by the mid-3rd millennium BC, goldworking was also present in the Aegean/Anatolian region. The styles differ (the Troy jewelry has its own character, possibly produced by Anatolian craftspeople), but the universal themes of adornment and status are clear. Another example in the Aegean is the Bronze Age Greece (Mycenaean civilization): though a bit later (c. 1600 BC), the Mycenaeans produced gold items such as the famous Mask of Agamemnon (a beaten gold funeral mask) and numerous gold cups, jewelry, and inlays found in the shaft graves at Mycenae. These finds, which occurred after the focus period of this article, underscore that wherever ancient civilizations arose, gold soon followed as a prized material.

Elsewhere, small early gold artifacts have been found in the Levant and Near East outside Mesopotamia. In a cave tomb in today’s Israel (Nahal Qanah Cave), a few gold beads have been dated to around 4500–4000 BC, roughly the Chalcolithic period. These may represent some of the earliest gold in the Near East, perhaps influenced by or parallel to the Balkan developments. Likewise, in Iran, gold objects appear in the Early Bronze Age at sites like Tepe Hissar and others, though not in great quantities. In China, the use of gold seems to have started later; the earliest Chinese gold artifacts (e.g., gold plaques and jewelry) are from the Shang and Zhou dynasties (2nd to 1st millennium BC), long after Varna and Ur, likely because early Chinese civilizations valued other materials like jade and bronze more highly initially. When gold did come into play in East Asia, it was also associated with royal burials and ritual (for example, the later Han dynasty burials contained gold dragons and belts).

What all these “other” finds reinforce is that the knowledge of gold’s properties and the desire to possess and display it emerged in different places independently. Because native gold is often found in riverbeds and is easy to work by pounding, it does not require the complex smelting technology that copper or iron do. So, Stone Age or Copper Age people in various regions could experimentally hammer gold nuggets and realize they could shape this intriguing shiny metal. Thus, multiple centers of early gold craftsmanship bloomed: the Balkans, Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus, Anatolia, and later the Americas and East Asia, each adding a chapter to the story of gold in human history.

Comparisons and Cultural Significance of Early Gold

From the foregoing survey, we can draw several enlightening comparisons about the role of gold in these ancient contexts:

- Universality of Appeal: Nearly every culture that encountered gold became entranced by it. Whether in a Varna grave, a pharaoh’s tomb, a Sumerian queen’s headdress, or a Peruvian offering, gold was universally associated with status, beauty, and possibly spiritual power. It’s notable that gold had no utilitarian value (it is too soft for tools or weapons, and too rare for building material), yet early humans devoted enormous effort to acquiring and fashioning it. This suggests that from the very dawn of metallurgy, gold was a symbolic and social material – a marker of prestige, a store of wealth, and an object in which to invest human creativity.

- Burial Traditions – Inclusion vs. Exclusion: A key difference we observed is in burial traditions. In Varna, Egypt, and early Mesopotamia, elite burials were loaded with gold, reflecting beliefs in an afterlife where such wealth either accompanied the dead or honored them. The lavish burials served to legitimize social hierarchy (only the important individuals received such treatment) and perhaps to appease gods or spirits with precious offerings. By contrast, the Indus Valley shows a cultural choice to exclude gold from burials, opting instead to keep it among the living. This could indicate different spiritual beliefs (perhaps the Indus people did not see a need to provide wealth for the afterlife in the same way) or a practical approach to inheritance and continuity of wealth in the community. Similarly, in some other cultures (like Neolithic Britain or Neolithic China), grave goods were modest despite the society’s ability to craft valuables, pointing to diverse ritual practices. The variation underscores that gold’s role was culturally defined, not intrinsically fixed: it could be a grave good in one society and a family heirloom in another.

- Ceremonial and Religious Associations: All these civilizations imbued gold with deep ceremonial meaning. In Egypt, it was explicitly linked to immortality and divinity, used in masks and coffins to transform the deceased into a god-like form. In Sumer and later Mesopotamia, gold adorned statues of gods and ritual instruments, suggesting it was thought pleasing to the deities. Varna’s cenotaphs with gold-decorated clay faces hint at ritual uses of gold in honoring those not physically present. The fact that even small-scale societies (like Jiskairumoko or the early tribal chiefs in Europe) used gold for personal adornment in burial or ceremonial contexts indicates that gold was often reserved for special, perhaps sacred, purposes. Gold’s incorruptibility (doesn’t tarnish or decay) likely impressed people as almost otherworldly – a fitting material to represent eternity or the divine. A similarity across many cultures is the association of gold with the sun or sky: its color and shine naturally bring to mind sunlight. Later Andean and Mesoamerican civilizations explicitly linked gold to solar deities, and it’s quite possible that earlier societies also subconsciously (if not explicitly) saw gold as containing the essence of light, life, or supernatural force.

- Technology and Craft Evolution: Technologically, working gold was often the first foray into metallurgy for many cultures because native gold can be shaped with minimal equipment. The Varna goldsmiths hammered and cut gold foil with stone tools, achieving beautiful results with simple techniques. As societies progressed, techniques evolved almost in parallel: by 2500–2000 BC, goldsmiths in Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus, and later Peru, had discovered annealing (softening gold with heat), forging, and even casting and soldering. We see that by Queen Hetepheres’ time (2600 BC), Egyptians were casting gold and using advanced joining methods, and the Sumerians around the same time were doing likewise. The Indus craftspeople could make hollow gold beads with soldered seams. Thus, there was a broadly similar trajectory: starting from hammering natural gold to developing melting and alloying skills, often within a millennium or two of the first gold artifact. Another fascinating point is that gold often predates copper smelting in some regions (since you can work gold cold, whereas to work copper, you generally must smelt ore). For example, in the Middle East, the first copper smelting happened in the 5th millennium BC, but if people had native gold, they might have been working it even earlier, just by hammering. This leads to the idea that gold could have been a catalyst for metallurgical knowledge – ancient smiths might have learned how to shape metals by practicing on gold and then applied those lessons to harder metals. In the case of Varna, they were already skilled with copper and gold concurrently, showing a full early mastery of metals. The shared technological innovations (like lost-wax casting appearing in both Egypt and Mesopotamia by the mid-3rd millennium) also raise the question of cross-cultural exchange of ideas. Trade routes certainly linked many of these regions (e.g., Egypt and Mesopotamia via Syria, Mesopotamia and Indus via Persia/Oman, etc.), so while gold itself was too scarce to be a common trade good at that time, the ideas of metalworking could have spread.

- Economic and Social Impact: Early gold artifacts also hint at broader economic patterns. The presence of exotic materials with gold, e.g., Varna’s Mediterranean seashells, Ur’s Indus beads, or Troy’s Anatolian gold during a time of expanding trade, suggests that gold was part of emerging long-distance exchange networks. Rulers who controlled gold resources or trade (like Egyptian pharaohs controlling Nubian mines, or later the Solomon legend of Ophir’s gold) enjoyed great power. Thus, gold contributed to the first wealth inequalities and perhaps even political centralization: who gets to own and be buried with gold? It’s usually kings, chiefs, and priests. The Varna finds are the first clear evidence of such inequality in prehistoric Europe. Gold may not have been a currency then, but it was a store of value and a means to display that value conspicuously. In a sense, gold was an early driver of what we might call proto-capital: it could be accumulated and passed on, enabling trans-generational wealth (as seen in the Indus where it was inherited rather than interred). Societies that learned to mine or acquire gold surely had an edge in prestige over neighbors that did not.

In summary, early processed gold served remarkably similar symbolic roles across diverse civilizations – a testament to how human beings, independent of each other, assigned extraordinary value to this metal. Yet each culture’s customs shaped the specifics of how gold was used: buried or hoarded, worn daily or reserved for rites, fashioned into minimalist beads or elaborate regalia. The differences are as instructive as the similarities, revealing the rich tapestry of human cultural innovation.

The Legacy of the First Goldsmiths

The discovery of the world’s oldest gold at Varna Necropolis has redefined our understanding of prehistoric societies, showing that advanced craftsmanship and social complexity emerged earlier than once assumed. Varna’s ancient goldsmiths, working 6,500 years ago, set a precedent for metalworking skill and ritual use of gold that would echo through time. In the ensuing millennia, Egyptians would gild the faces of their pharaohs, Mesopotamians would send their queens to the afterlife with glittering headdresses, and distant peoples in the Andes would hammer golden nuggets into offerings for their dead – all unknowing inheritors of a fundamental human fascination with gold that began in deep antiquity.

Today, gold remains a powerful symbol of wealth and status, from jewelry to monetary reserves, underscoring a continuity with our ancient past. The earliest processed gold artifacts are more than museum pieces; they are clues to the dawn of human ingenuity and the birth of economic and religious expression. They remind us that long before written history, across continents, people found meaning in the soft glow of hammered gold. In a real sense, the golden treasures of Varna, the Nile, the Euphrates, the Indus, and the Andes form a connected story – a story of humanity’s first steps into metallurgy and the enduring glitter of the noble metal that captures our imagination to this day.

References

- Smithsonian Magazine (2016) – “Mystery of the Varna Gold”: A journalistic account of Varna’s discovery and significance, discussing the rich Grave 43 and its implications for understanding prehistoric social hierarchy – smithsonianmag.com.

- Varna Museum / VisitVarna.bg – Varna: The Oldest Gold Treasure: Describes the Varna treasure, the number of artifacts (around 3,000) and total weight (6 kg), and the technological sophistication (hammering, piercing, cutting) of the gold objects – bulgaria-guide.com | visit.varna.bg.

- Varna Necropolis – Wikipedia: Provides chronology and context for Varna culture, including the statement that Grave 43 contained more gold than all other known sites of the same epoch combined – en.wikipedia.org.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art – “Gold in Ancient Egypt” (Essay): An authoritative source on Egyptian gold, noting earliest gold artifacts in Egypt in the 4th millennium BC (preliterate period) and techniques like lost-wax casting and electrum usage over time – metmuseum.org.

- Egypt Tours Portal – “The Gold of Ancient Egypt: Symbolism, Wealth, and Immortality”: Describes the religious significance of gold in pharaonic funerary practice (e.g., Tutankhamun’s mask) and outlines goldsmithing techniques mastered by Egyptians by the Old Kingdom – egypttoursportal.com.

- Royal Cemetery of Ur – Wikipedia: Details the gold artifacts from the Sumerian tombs at Ur, including jewelry, weapons, and vessels, and evidence of advanced techniques (e.g., casting of an electrum dagger, gold helmets, twisted-wire handles on cups) – en.wikipedia.org.

- Harappa.com (Jonathan Mark Kenoyer) – “Ancient Indus Ornaments”: Illustrates types of Indus Valley gold ornaments and notes that Indus gold jewelry was not buried with the dead but rather kept and hidden in houses, indicating cultural practices of inheritance – harappa.com.

- The Tribune (Pakistan) – “Mohenjo Daro necklace: two halves of a whole” (2023): Describes a famous 4500-year-old gold and semi-precious stone necklace from Mohenjo-daro, its division between museums, and its sophisticated construction (hollow gold beads made by soldering) – tribune.com.pk.

- LiveScience (2008) – “Oldest Gold Artifact in Americas Found”: Reports the discovery of the 4,000-year-old gold bead necklace at Jiskairumoko, Peru, including its context (a humble burial), date (circa 2150–2000 BC), and the primitive hammering technique used to create the beads – livescience.com.

- PNAS Journal (2008) – Aldenderfer et al.: “Four-thousand-year-old gold artifacts from the Lake Titicaca basin” (as referenced by LiveScience) – The academic source detailing the Jiskairumoko gold find, signaling early social complexity in that region – livescience.com.

- Lapham’s Quarterly – “Digging Up Troy”: Confirms the dating of “Priam’s Treasure” from Troy II to about 2400 BC, dispelling its association with later Homeric Troy and highlighting the cache of early Anatolian gold artifacts – pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.