Understanding Bulgaria’s wine regions can be confusing, with multiple layers of classification evolving over time. We are committed to making this the most comprehensive resource available, clarifying how today’s PDO and PGI system emerged from centuries of tradition, scientific research, and regulatory changes. Nowhere else on the internet offers such a detailed, structured breakdown of Bulgaria’s wine zoning, making this article essential reading for wine professionals and enthusiasts alike.

Ancient & Medieval Wine Traditions

Wine has been made in modern Bulgaria for over 5,000 years, dating back to the ancient Thracians. Thracian tribes, inhabiting what is now Bulgaria, were famed in antiquity for their wine – Homer’s Iliad mentions ships of Thracian wine. Aristotle noted the mythical wines of Thrace, which were so thick they had to be diluted. In Thracian culture, wine was central to religion and ritual; the first known wine deity, Zagreus, originated in the Thracian pantheon before evolving into the Greek Dionysus. Archaeological finds across Bulgaria – gold and silver rhytons, amphorae, and the famed Panagyurishte Treasure – testify to sophisticated wine rites and the high esteem of wine in Thracian society.

Following Thrace’s legacy, winemaking persisted through Roman rule and the early medieval Bulgarian states. Roman influence spurred vineyard expansion, though the collapse of Roman power saw some decline. By the First Bulgarian Empire (c. 9th century), viticulture was so widespread that Khan Krum allegedly ordered a law to uproot all vines to curb drunkenness. This drastic measure was short-lived, and viticulture rebounded even as the Bogomils (a medieval Bulgarian sect) preached temperance. In fact, medieval Bulgarian wine was valued abroad – records note that good wine was also exported to the European marketplace during the Middle Ages. Bulgarians kept wine traditions alive throughout Ottoman rule (15th–19th centuries). Christians were permitted to cultivate vines for communion wine, allowing monastic vineyards and local cellars to endure. By the 18th century, a wine revival was underway: a wealthier Bulgarian Christian class spurred demand for quality wine, and Bulgarian reds from the Black Sea coast began finding export markets. Even the Muslim Ottoman elite, barred from wine by religion, prized Bulgarian dessert grapes, which helped preserve a diversity of grape cultivars. Despite periods of disruption – from Krum’s decree to religious prohibitions – wine remained embedded in Bulgarian culture and economy through antiquity and the medieval era.

19th–20th Century Developments

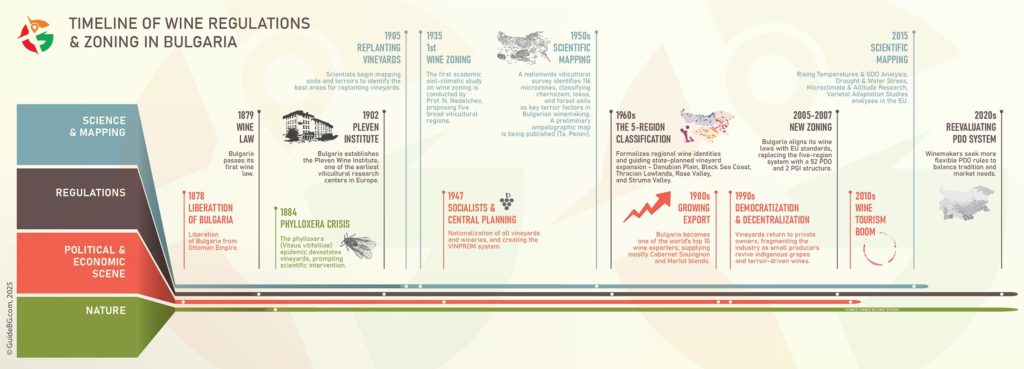

After the Liberation from Ottoman rule in 1878, Bulgaria’s wine industry entered a phase of rapid modernization. By the late 19th century, vineyard plantings had expanded to around 115,000 hectares (in 1897) as Bulgarian vintners eagerly applied European techniques. However, the phylloxera vine pest struck in 1884 (first noted near Vidin in the northwest) and devastated most traditional vineyards. In response, the young Bulgarian state acted swiftly: the Ministry of Agriculture invited French viticulture expert Pierre Viala to advise on recovery. Viala toured Bulgarian wine regions and recommended grafting European grape varieties onto phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks – the proven solution already used in France. He also urged institutional support for viticulture, leading to the founding of a dedicated vine and wine research station in Pleven. 1902 Bulgaria established the National Institute of Viticulture and Oenology in Pleven, one of the world’s earliest viticulture institutes (preceded only by those in Russia, Italy, France, and Hungary). Systematic replanting on resistant rootstock began in 1906 and accelerated post-World War I, laying the groundwork for a renaissance in Bulgarian wine.

The 1920s–1930s were a golden age for Bulgarian viticulture. Wine cooperatives proliferated, transforming winemaking from small family endeavors into organized industry. With technical help from Western Europe (notably Austria and France), modern wineries were built in traditional wine towns – Suhindol, Lovech, Pleven, Melnik, Plovdiv, Chirpan, Sliven, and others. By the 1930s, the vineyard area had doubled to around 200,000 hectares. Bulgarian wines earned international acclaim, winning medals at world expositions alongside the country’s famous rose oil. This period also saw the first academic attempts to map and classify wine regions. For example, Prof. Nedelchev’s 1935 study identified five distinct vine-growing zones, foreshadowing later official regionalization. We mentioned this zoning when profiling modern wine regions (see Novo Selo profile).

After 1944, Bulgaria’s wine industry was reorganized under socialism. All wineries were nationalized and consolidated into state-controlled enterprises. Production was geared toward high-volume, inexpensive wine for the domestic and Soviet bloc markets. Native grape diversity suffered as central planners mandated mass plantings of high-yielding international varieties (such as Rkatsiteli, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay, Aligoté and others) to boost output. By the 1960s, Bulgaria had become one of the world’s largest wine exporters, but much of its wine was simple table wine; in the 1970s–1980s, a pivot toward quality began – the regime invested in prestigious red varietals and modernized winemaking, leading to improved wines that entered Western markets. By the late 1980s, Bulgaria was a major wine supplier to the UK, Germany, and Japan while still sending about 90% of exports to the USSR/Russia. However, Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign (during so-called Perestroyka) in the mid-1980s hit Bulgarian vineyards hard, forcing the uprooting of some vines and a shift to even cheaper wines.

The collapse of communism in 1989 brought tumultuous change. State wineries were privatized, and the land was restituted to thousands of small owners, fragmenting vineyards that had been managed collectively. The early 1990s saw a sharp decline in production and quality – many vineyards were abandoned or poorly tended, and wineries struggled to source quality grapes from a suddenly atomized grower base. Bulgarian wine virtually disappeared from many export markets during this time. By the late 1990s and 2000s, recovery was underway. Foreign investment and EU pre-accession programs (SAPARD, PHARE) helped modernize equipment and replant vineyards. A new generation of boutique wineries emerged in the 2000s, focusing on quality over quantity. These small producers and renewed cooperatives began to revive indigenous grape varieties (like Mavrud, Shiroka Melnishka Loza/Broadleaf Melnik, Pamid, and Dimyat), even as international varieties remained popular. By the time Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, its wine industry had transitioned from a volume-driven model to a quality-focused, entrepreneurial landscape, albeit one still overcoming the legacy of the 1990s downturn.

Scientific & Research Contributions to Terroir and Zoning

Science and research have long underpinned the evolution of Bulgaria’s wine regions. Early on, the French expert Pierre Viala’s intervention (1880s) brought Western scientific solutions to Bulgaria’s phylloxera crisis. The Pleven Wine Institute (1902) established a center for viticultural research, experimentation with grafted vines, and preserving grape germplasm. Throughout the 20th century, Bulgarian viticulturists and agronomists conducted extensive studies of climate, soils, and grape genetics. For example, in the 1930s, Prof. Nikola Nedelchev led one of the first comprehensive terroir studies – in 1935, he proposed dividing Bulgaria into five viticultural zones based on climate and soil patterns. Nedelchev’s regions (Northern/Danubian, Rila-Rhodopean, Sub-Balkan, Black Sea, and Melnik) were defined by observing which grape varieties thrived in different locales. Although rudimentary by modern standards, this work recognized that factors like winter cold in the Danube Plain or Mediterranean warmth in the southwest fundamentally shape wine styles.

During the socialist era, terroir research became more systematic. In the 1950s, the government conducted a comprehensive survey of wine-growing areas, cataloging local grape cultivars and analyzing soil and climate data nationwide. This research led to detailed agroecological mapping: scientists delineated 116 micro-zones (micro terroirs) and identified the grape varieties best suited to each. As one study notes, “specialization of each wine-growing region is determined based on detailed soil surveys and long-term climate observations”, ensuring that varieties are matched to their optimal terroir. Bulgarian soil scientists (from the National Soil Survey and academia) contributed by classifying the country’s diverse soils – from the chernozem black soils of the north to the cinnamon-forest soils of the south – and evaluating their viticultural potential. By combining these soil maps with climatic data (temperature, frost risk, rainfall), researchers defined precise agro-climatic indicators for viticulture in each region.

Crucially, the findings of these studies were used to shape official wine region delimitation and vineyard planting policies. For instance, mid-century research confirmed that the hot, dry Struma Valley (southwest) is uniquely suited to late-ripening grapes like the local Melnik vine, whereas the cooler Rose Valley (Sub-Balkan) excels with aromatic whites like Red Misket – insights that guided regional specialization. Bulgaria’s viticultural research institutes (in Pleven and later branches in Plovdiv and Sofia) also maintained ampelographic collections of native grape varieties, safeguarding them through the socialist era when international varieties dominated. This preservation proved valuable when, in the 21st century, winemakers began reviving heirloom varieties using plant material and knowledge from these institutes.

In recent decades, scientific analysis has further refined the understanding of Bulgarian terroir. Studies by the Institute of Viticulture and Enology and the Executive Agency on Vine and Wine applied GIS and remote sensing to update vine zoning maps, identifying new meso-climates suitable for quality wine. Terroir analysis projects (often in collaboration with EU partners) have evaluated how climate change might shift grape suitability in Bulgaria, predicting warmer growing seasons, especially in traditionally cooler northern areas. Ongoing soil research by organizations like National Soils assists vintners in site selection – for example, providing digital maps that pinpoint ideal soil parcels for planting specific varieties (considering soil pH, depth, water retention, etc.).

Wine Zoning & Classification Evolution

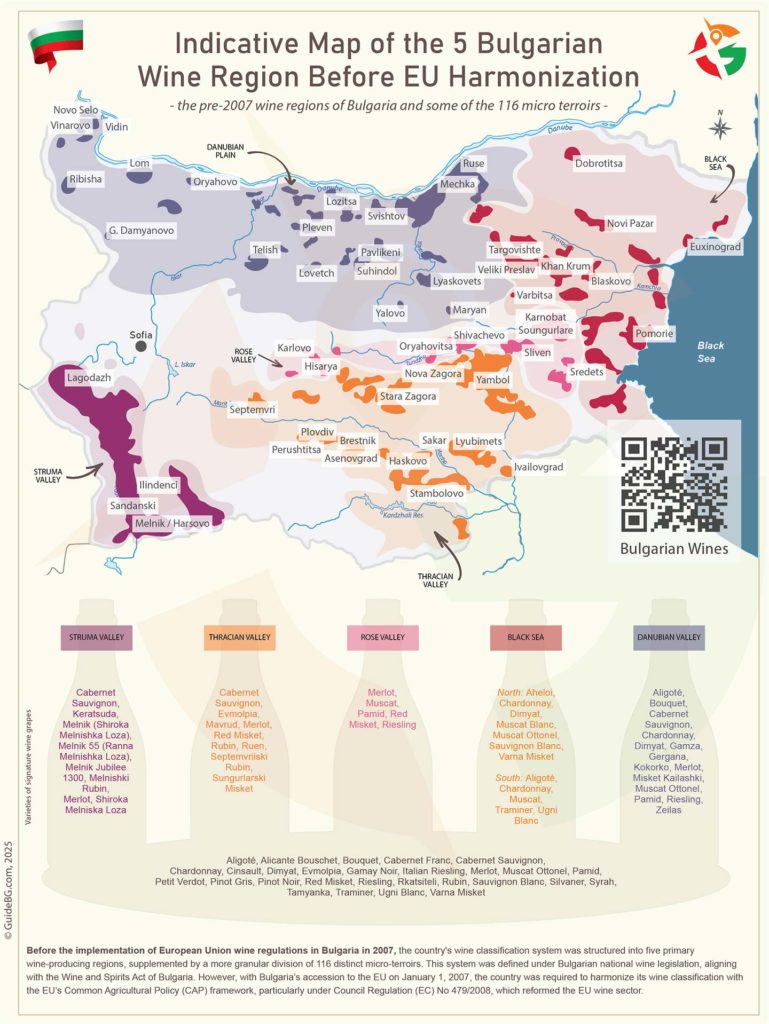

The formal delineation of Bulgarian wine regions has evolved with the country’s political and scientific history. Traditional regional divisions took shape by the mid-20th century. Building on earlier academic proposals, in 1950-1951, the government issued a decree establishing five major wine regions: North Bulgarian (Danubian Plain), East Bulgarian (Black Sea Coast), Sub-Balkan (Rose Valley), South Bulgarian (Thracian Lowlands), and Southwest (Struma Valley/Melnik). These zones were defined by broad climatic and geographic criteria – for instance, the Danubian Plain region covered the entire northern half of the country from the Danube River south to the Balkan Mountains. At the same time, the Thracian Valley (Lowlands) encompassed most of southern Bulgaria’s plains. The intention was to group areas with similar growing conditions and thus encourage the cultivation of appropriate grape varieties. In the 1950s–60s, authorities initially recognized four primary regions (North, South, East, and Southwest), with the Rose Valley considered a distinct sub-region. By 1960, this was codified in regulation (Council of Ministers Decree №162, 1960), which explicitly listed five viticultural regions aligned closely to the earlier five-fold scheme. Each region was divided into dozens of local microregions, reflecting the 116 districts identified by scientists for specific grape types.

This mid-20th-century regional scheme remained in place for decades and is the basis of the five traditional wine regions often referenced in Bulgarian wine literature. Notably, those five correspond to distinct terroirs:

- Danubian Plain (Northern) – continental climate with hot summers and cold winters, historically known for reds like Gamza (Kadarka) and whites like Aligote and Riesling.

- Black Sea (Eastern) – maritime climate, milder winters, and long autumns, specializing in white grapes (Dimyat, Muscat Ottonel, Riesling, Chardonnay) that benefit from the humid sea air.

- Rose Valley (Sub-Balkan) has a temperate climate in the foothills south of the Balkan Mountains. It is famous for the Red Misket grape and Muscat, which yield delicate, aromatic whites and rosés.

- Thracian Lowlands (Southern) – a warm inland plain with a moderate continental climate, historically the heartland of robust reds like Mavrud, Pamid, and later Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.

- Struma Valley (Southwestern) – dry, Mediterranean-influenced climate, uniquely suited for the Broad Leaved Melnik vine and other late-ripening reds, producing lush, spicy wines.

Each region developed its profile of grape varieties and wine styles under the centralized wine industry. For example, during the 1970s–80s, Thracian Lowlands became synonymous with Bordeaux varietals (Cabernet and Merlot) and the native Mavrud. In contrast, the Black Sea coast was planted heavily with Riesling, Dimyat, and Traminer for white wine and sparkling base. The Struma Valley remained small but was recognized for its unique Melnik wines, and the Rose Valley/Sungurlare area continued to cultivate the Red Misket for which it’s named.

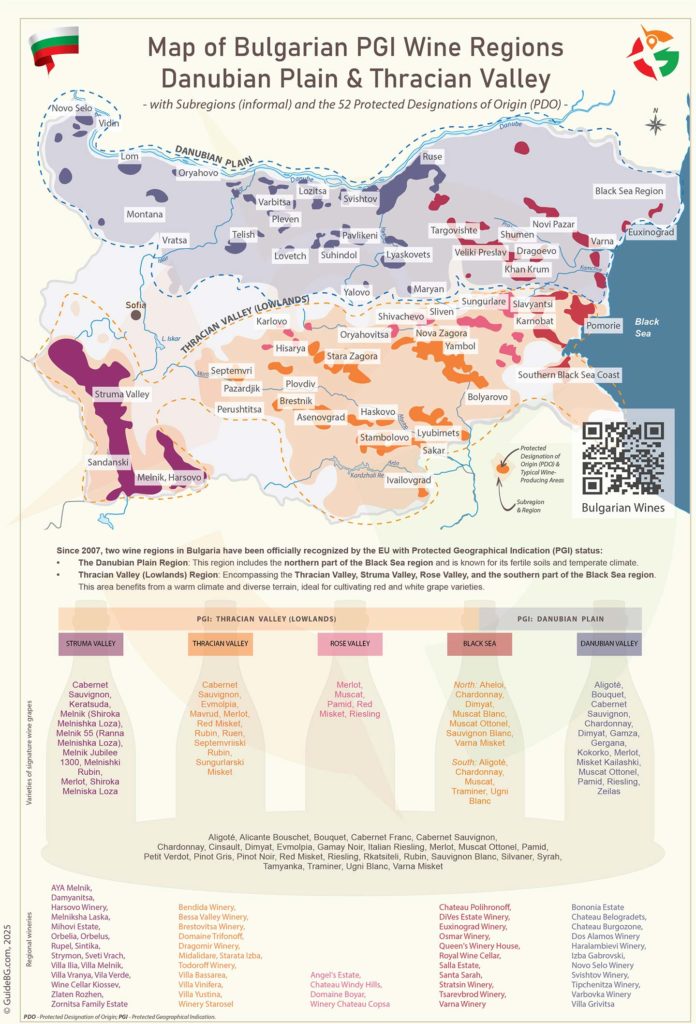

With the end of communism and Bulgaria’s pursuit of EU membership, the country’s wine classification system underwent significant reform. In preparation for EU alignment, a new Wine Law in 2005 redefined Bulgaria’s wine regions to fit the European scheme of Protected Geographical Indications (PGI) and Protected Designations of Origin (PDO). Since August 16, 2005, Bulgaria has officially been divided into two large PGI regions for wine labeling: PGI Danubian Plain in the north and PGI Thracian Valley (Lowlands) in the south. The traditional five regions were essentially consolidated into two super-regions split by the Balkan Mountains (Stara Planina range). The PGI Danubian Plain covers all of Northern Bulgaria, including the northern part of the Black Sea Coast. At the same time, the PGI Thracian Valley encompasses Southern Bulgaria, including the Struma Valley in the southwest and the southern Black Sea coast. These PGIs, broadly analogous to France’s IGP or Italy’s IGT, allow producers to market wines with a recognized regional origin. As Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, 52 PDOs were registered (analogous to appellations like AOC or DOC) for specific localities with distinctive wine traditions. Examples of these PDO designations include Sakar (a hilly area in the southeast Thracian region known for Cabernet Sauvignon), Suhindol and Svichtov (towns in the Danube region with long winemaking histories), Melnik (after the town and its famed grape in the Struma Valley), Khan Krum (a Black Sea area named after the medieval ruler), among many others. However, many of the 52 PDO names remain obscure or seldom used in commerce.

This transition reflects a shift from the old national classification to EU-standard categories: under the EU system, “Table wine” and “Quality wine” categories were replaced by Wine without GI, PGI, and PDO. Bulgaria’s two PGIs became the main geographical indications on exported wines (e.g., a bottle labeled “PGI Thracian Lowlands” for a wine from any southern sub-region). Theoretically, the PDOs would designate more tightly defined terroirs with stricter production rules. The adoption of PDOs has been slow and limited – they account for under 1% of Bulgaria’s wine production. Many producers found the PDO requirements too stringent or impractical (for instance, specific PDO rules dictate vine training systems, row spacing, or yield limits that are hard to implement). Thus, while Bulgaria has dozens of micro-appellations on the books, few wineries use them on labels, preferring the more flexible broad PGIs or even marketing wines without a GI.

Meanwhile, the legacy five-region classification did not disappear overnight; domestic institutions and industry groups often still refer to the traditional regions for viticultural guidance and marketing. As many commentators noted – other more traditional geographic designations are still used by both producers and regulatory organizations despite the official EU scheme. For example, the 2020 Ministry of Agriculture’s National Vineyard Structure Survey cites data from the five traditional regions. Wine tourism promotions frequently highlight the Struma Valley or Rose Valley by name, even though those are subsumed under the PGI Thracian Valley (Lowlands).

Bulgaria’s wine zoning evolved from an initial five-region schema based on climate and soils to a simplified EU-compliant system of two massive regions (PGIs) plus many fine-grained PDOs. This has created some disconnect between the nuanced reality of Bulgaria’s terroir and bottle labels. Ongoing efforts aim to bridge this gap – for instance, industry discussions have proposed re-introducing more specific region indications (within the PGIs) to reflect better distinct areas like the more fabulous Northern Black Sea coast vs. the hotter Sakar area, which are currently lumped together. The classification evolution continues as Bulgaria finds the balance between honoring traditional regional identities and meeting international (EU) regulatory frameworks.

Current Wine Regions & PDO/PGI System

Today, Bulgaria’s wine landscape is officially defined by the EU PGI/PDO system, but the practical understanding of wine regions involves both the new and the old classifications. Two PGIs (Protected Geographical Indications) blanket the country. The PGI Danubian Plain (often just Danube Plain) spans northern Bulgaria, from the Serbian border across the Danube River’s southern bank to the Romanian and Black Sea border. Within this northern PGI are varied sub-zones – including the flat, fertile Danube River plain and the Northern Black Sea coastal area around Varna and Dobrich.

The climate across the Danubian PGI is temperate-continental: cold winters, hot summers, and moderate precipitation. This region excels in white wines and lighter reds. Over half of Bulgaria’s white wine grapes are grown here. Notable varieties include Dimyat (an ancient local white), especially near the coast, Muscat Ottonel, Rkatsiteli, Chardonnay, and Sauvignon Blanc for whites. Reds in the Danubian area tend to be fresh and fruity; the signature local red is Gamza (Kadarka), particularly in the northwest (e.g., around Pleven), producing Pinot Noir-like light reds. International reds like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot are also widely planted and often blended with indigenous grapes. The Danubian Plain PGI is also known for quality sparkling wines (around Shumen and Varna) thanks to the cool conditions and traditional varietals like Chardonnay and Riesling.

The PGI Thracian Lowlands, covering southern Bulgaria, is the country’s powerhouse region, accounting for roughly 75% of Bulgaria’s vineyards. This vast area comprises several distinct terrains: the western Thracian plain near Plovdiv (birthplace of the famed Mavrud grape), the eastern Thracian region and Sakar Mountain foothills near Haskovo, the Rose Valley between the Balkan and Sredna Gora ranges, the southern Black Sea area around Burgas, and the Struma River Valley in the southwest. The climate is generally warmer and sunnier than the north, with some Mediterranean influence creeping into the far south. The Thracian PGI is predominantly a red wine region – nearly two-thirds of its vineyard area is planted to red varieties, producing robust, full-bodied wines. Key grapes include the flagship Mavrud, an ancient Bulgarian red that thrives in the Plovdiv and Pazardzhik area, giving deep, tannic wines regarded as Bulgaria’s finest local reds. Rubin (a mid-20th-century Bulgarian cross of Nebbiolo and Syrah) is another specialty red in Thrace, valued for its dark color and spice. The southwest Struma Valley portion of the PGI is home to Broad-Leaved Melnik (Shiroka Melnishka) and its hybrid Melnik 55 – unique local reds with peppery, rustic character found only in that corner of Bulgaria. International red grapes – Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, and Cabernet Franc – also flourish across Thrace’s terroirs and have in fact dominated new plantings, making up about one-third of all Bulgarian vines. Many of Bulgaria’s acclaimed contemporary wines are Cabernet-Merlot blends or varietals from this PGI, often with a dash of Mavrud or Rubin to lend regional identity.

White wine production in the Thracian Lowlands is smaller but not absent – Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc appear in cooler pockets (e.g., near the Balkan foothills or higher elevations of Sakar), and Muscat and local Red Misket are cultivated in the Sub-Balkan valley (Sungurlare and Karlovo areas) for aromatics. The Rose Valley sub-region in particular, while officially within the Thracian PGI, is celebrated for its whites and rosés with delicate floral notes (the name comes from the rose oil industry there, but it also suits the wines’ fragrance). Meanwhile, along the southern Black Sea coast, wineries exploit the maritime climate for crisp whites and fresh reds (the Pomorie area, for example, produces delicate dry whites from Dimyat and Traminer, and the Karnobat area is known for Cabernet).

Beyond these broad strokes, Bulgaria’s 52 PDOs represent specific localities with traditional reputations. Each PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) has the standard strict regulations on permitted grape varieties, minimum ripeness, yield limits, and winemaking practices (often including aging requirements or wood use). However, as mentioned, relatively few producers currently navigate the bureaucratic hurdles to label their wines with these PDO names. One reason is that the broader PGI categories already confer a general regional identity without the production constraints. Another is that many of the PDOs are not yet strongly marketed or recognized by consumers, making the effort less rewarding. An illustrative case is PDO Sakar: while the region of Sakar is well-known among enthusiasts (for powerful reds, especially Cabernet and Syrah, grown on its sunny, rocky slopes), most Sakar wineries opt to label their bottles “PGI Thracian Valley” (or even just the vineyard geographical name, or winemaker’s name) rather than as a PDO, to avoid restrictive rules and because PGI Thracian Valley itself has begun to earn international recognition for quality.

Quality Hierarchy

In Bulgaria’s current system, PGI wines are considered “regional wines” of quality, and PDO wines are meant to be the top tier (similar to France’s AOC). Additionally, Bulgarian law allows special designations for wine aging and quality terms like Reserve (1-year oak + 6 months bottle for reds) and Special Selection, which some producers use alongside the GI. These terms, however, are producer-specific and not tied to regions. Overall, PGI Danubian Plain and PGI Thracian Valley have become the workhorses for Bulgarian wine exports and marketing, splitting the country into a North vs. South identity. At the same time, local winegrowers still refer to the five traditional regions when talking about climate and grapes – for instance, a winemaker might say, “This vineyard is in the Struma Valley” to emphasize its unique hot climate, even though on paper, the wine is Thracian PGI. The current regulatory framework is thus a layered mix of old and new: the EU-approved terms on labels (PGIs/PDOs) and the colloquial/historical terms that insiders and locals use.

Future Outlook & Trends

Bulgaria’s wine region classification is still evolving, and further reforms are on the horizon to better balance tradition, quality, and marketability. One likely development is a return to smaller geographical indications as the limitations of the two-PGI system become evident. Many in the industry argue that the current PGIs are too broad and don’t reflect the climatic or soil differences on the ground. For example, the hot, arid Struma Valley in the southwest and the maritime Black Sea coast in the east have little in common, yet both are lumped into the PGI Thracian Valley (Lowlands). In response, the Bulgarian Wine Executive Agency and industry groups have drafted a new National Wine Strategy (2025) that tentatively outlines a five-region system (similar to the historical one) to be officially recognized within the PGI framework. This suggests that terms like “Rose Valley”, “Struma Valley”, “Black Sea Region” may regain legal status or at least be used as defined sub-zones under the two main PGIs. The goal is to help wineries better market their unique regional identities and terroir distinctions, which are especially important for attracting wine tourism and niche export markets.

Regarding the PDOs, there is a push to either streamline PDO regulations or establish new, more practical appellations. Many of the 52 PDOs are currently unused because of overly strict rules (e.g., rigid vine spacing requirements) or bureaucratic red tape. Producer associations in areas like South Sakar and Melnik/Struma have expressed interest in creating new PDOs or tweaking existing ones to fit their terroir and practices better. If these efforts succeed, we may see, for instance, a PDO Struma Valley that consolidates the tiny Melnik PDOs and sets reasonable standards that most local wineries can meet – thereby encouraging broader adoption. Simplifying the appellation system can also help Bulgarian PDOs gain recognition internationally; at present, a wine labeled with an obscure village name means little to consumers, but a PDO labeled “Melnik Valley” or “Sakar Mountain” might carry more storytelling power. The Bulgarian government will likely adjust laws to make PDO usage more appealing to elevate Bulgaria’s reputation for fine, origin-specific wines.

Climate Change

Warming temperatures and shifting weather patterns are expected to particularly impact the southern wine regions. Climate models project that by the mid-21st century, Bulgaria may see average temperature increases of 2 – 3°C and more frequent droughts in some areas. This could push growers to adapt by exploring higher-altitude vineyards (e.g., in the Balkans foothills or Rhodope mountains) and changing varietal portfolios. Grapes like Syrah, Mourvèdre, or other heat-tolerant Mediterranean varietals might become more common in Thrace and Struma Valley if summers get hotter. Conversely, traditionally cool northern areas might ripen late varieties more consistently – potentially making the Danubian Plain suitable for grapes like Cabernet Franc or even expanding Melnik plantings further north. Researchers and wineries are already collaborating on climate resilience: testing irrigation in arid zones like Sakar, selecting drought-resistant clonal material, and reviving hardy local grapes (such as Dimyat and Rubin) known to withstand heat. The zone maps may be redrawn in coming decades to account for these shifts, with new micro-regions identified at higher elevations. Bulgaria’s long history shows adaptability – from surviving phylloxera to restructuring after communism – and its wine regions are expected to adapt to environmental challenges.

On the market side, Bulgaria is positioning its wine regions as part of its national brand. Ongoing efforts in wine tourism highlight each region’s unique heritage: visitors can tour Melnik’s sandstone cellars, attend a Rose Festival wine tasting in the Rose Valley, or explore Thracian tombs and wineries around Plovdiv – all experiences tying wine to cultural identity. Emphasizing indigenous varieties by region is a key strategy, e.g., branding the Struma Valley as the home of Melnik or the Thracian Valley (Lowlands) as the land of Mavrud.

Bulgaria’s wine regions have come full circle, from ancient Thracian vineyards to modern PGIs, always influenced by the interplay of nature, science, and history. The country is blessed with varied terroirs and a rich wine legacy, and the evolving zoning and classification aims to capture that diversity. With continued research, responsive regulations, and passionate winemakers, Bulgaria is poised to refine its regional identities further – marrying millennia of tradition with modern classification. The next decade could see a more terroir-driven map of Bulgarian wine, one that wine lovers worldwide will recognize and appreciate for its unique mosaic of climates, soils, and flavors.